For the first hundred years, Lady Liberty stood proud and tall, but not without those who wanted to reclothe her … prematurely. In 1906, for example, Congress appropriated $62,000 to paint her. Why? Because some politicians were distressed that she had turned green. This brought about a bit of outrage. Newspaper reports at the time said this would be "sacrilege." One of them quoted Joseph Mitchell of the John Williams Company as saying: "Copper can't rust. Removing the patina would be vandalism for which there would be no excuse."

Statue of Liberty with Fully Developed Patination

Statue of Liberty with Fully Developed PatinationFortunately, the plan failed. At the turn of the century, it took longer to form the color we see today's New York air, it would take about 10 years to achieve, but at the turn of the century, it was nearly 25 years before the patina was full-blown.

And, America loved the blue-green look of the Lady.

In fact, in a 1925 editorial, the New York Sun said: "Salt air has given 'Miss Liberty' her present sea-green complexion, so often remarked from passing liners. Deep-sea winds brawling up the Narrows from Sandy Hook have oxidized her copper and provided a weatherproof coating, which, her custodians say, will make her last forever … or as long as stone and metal hold together."

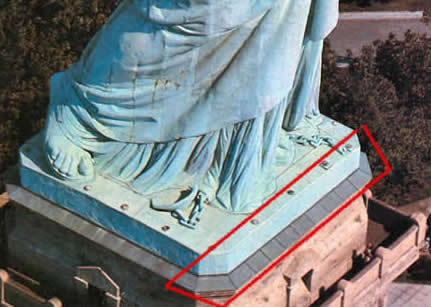

However, in 1937, on the 50th anniversary of the statue, there would have to be repairs made to the stone. Water had been seeping into the pedestal. As a result, the WPA constructed a 250-foot copper apron (a kind of cap flashing) over the pedestal. As the maintenance manager said at the time: "In the future, Miss Liberty's feet will be kept dry with this protective coating."

Statue Base with the Added Apron

Statue Base with the Added ApronNow as her first centennial approached, there were about a dozen reasons why our First Lady of Metals needed to be reclothed. They included considerations for visitors' access and comfort, safety, appearance, and, of course, needed repairs.

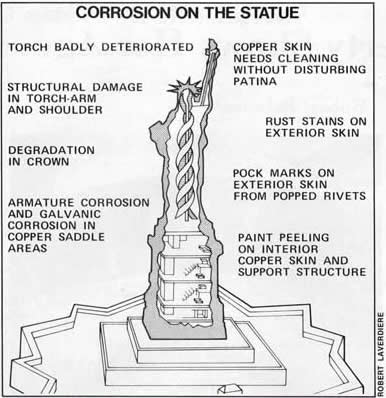

The most important of the repairs related to corrosion and included:

- The interior of copper skin.

- Weakening of support structure for the arm holding the torch.

- Deterioration of the torch, itself.

- Corrosion of the iron armature, and in particular, where it was attached to the copper skin.

- And, the exterior copper skin.

Skeleton with Call-outs for Repair Items

Skeleton with Call-outs for Repair ItemsIn 1984, Peter Dessauer, the historical architect for the National Park Service who led the restoration project, said, that "despite deterioration of other metals, the copper skin of the Statue of Liberty has remained virtually intact." But repairs were needed. The interior of the copper shell and the iron armature had received several layers of protective coatings over the years, including coal tar, aluminum and lead. Those coatings deteriorated and peeled, providing pockets where moisture was trapped and corrosion could occur.

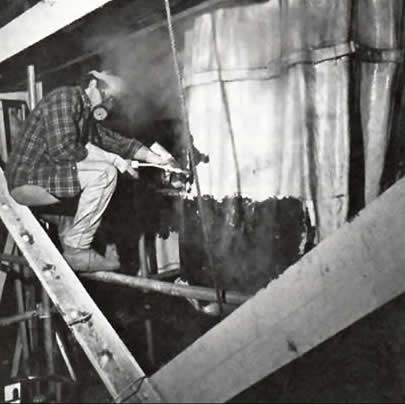

Detail of Interior Corrosion

Detail of Interior CorrosionTo strip away the old coatings (an estimated 10 layers), the surfaces were first broken down with liquid nitrogen at minus 350ºF, and then blasted at 50 psi with 100 tons of coarse-grain sodium bicarbonate. The method left no corrosive by-product.

However, because sodium bicarb attracts water, dryers in the compressor and at the nozzle were required. The newly cleaned surfaces were finally treated with benzotriazole to help prevent further crevice corrosion.

Interior Repair with Liquid Nitrogen

Interior Repair with Liquid NitrogenThe puddled-iron was blasted with an aluminum oxide abrasive, after which an inorganic water-based zinc primer was applied as a rust inhibitor. That was followed by a polyurethane top coat to provide graffiti protection.

Blasted with Aluminum Oxide

Blasted with Aluminum Oxide