Peter Diepenbrock: Bringing Copper's Classic Beauty to Modern Sculptures

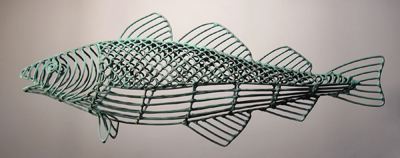

Atlantic Cod by Peter Diepenbrock, 18" high x 60" long x 5" deep.

Atlantic Cod by Peter Diepenbrock, 18" high x 60" long x 5" deep.Photograph courtesy of Peter Diepenbrock

While studying industrial design at Rhode Island School of Design in the 1980’s, Peter Diepenbrock had a revelation; there was a professional place in the arts better suited for him.

“From ideation to production, I find it very interesting,” Diepenbrock says. “But the fine artist in me wants to take it into a different direction and go into a sculptural path, which is non-functional. When it starts with the functional part is where I lose interest because it becomes more of an engineering concern.”

Diepenbrock, who has specialized in site-specific sculptural work for the past 30 years, is most interested in abstract conceptualization. He prefers to use visual metaphors and explore concepts that are less defined. While most of his forms are abstract, functional aspects still have to be taken into consideration for his work, most of which is done on a commission basis.

“You can have non-functional sculptures sitting in a plaza and it does then have some functional considerations to play into it, but they are not as literal” he says. “It’s more about landscape design and pedestrian flow, whether or not people can have access to sit or climb on it, whether it will be lit at night or not.”

When it comes to material preferences, Diepenbrock says he is typically drawn to use copper and bronze, and metals as a general category.

“They can stand on their own for quite some time,” he says of what draws him.

For one piece he might choose to use stainless steel for its anti-corrosion capability and aesthetics related to reflecting light, or choose copper or bronze for reasons associated with color.

“You can get the most beautiful greens with patinas, which are a more natural coloration versus the inherent colors of other metals,” he says. “That is the beauty of copper. With the different patinas you can change the color all over the spectrum. The patinas give it an Old World feeling.

Diepenbrock uses thin-gauged copper to make replications of his sculptures to serve as small-scale presentation models. He might use copper plumbing tubing to make art shapes, such as a "suspended sculpture.”

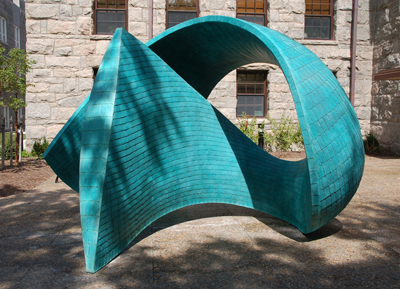

Torsion III by Peter Diepenbrock, in the collection of the University of Rhode Island, 10' high x 14' long x 11' deep.

Torsion III by Peter Diepenbrock, in the collection of the University of Rhode Island, 10' high x 14' long x 11' deep. Photograph courtesy of Peter Diepenbrock

“Copper is great because of its softness,” he says. “It has a soft warmth. You can weld it, but it’s not as happy to be welded as bronze.”

Diepenbrock sources his copper locally at risd: store3D in Providence, Rhode Island.

“I go to Atlas Metals in Colorado for the bronze,” he said. “They are one of the only very few places in the U.S. to distribute silicon bronze.”

Diepenbrock describes the labor involved in making his sculptures as “very intense”, which has him favoring the concept development stage of the whole process.

“It can be exhausting really,” he says of the labor, “But it’s satisfying to have direct control over it.”

In very rare cases, he’ll subcontract big, thick parts out to a metal fabricator.

“That is less than 10% of what I do,” he says. “90% I do myself as a one-man band with a part-time assistant.”

Most of the inspiration for Diepenbrock’s work, which he makes at his studio in Jamestown, RI, comes from the site itself. Diepenbrock also finds inspiration in the way physicists describe the world.

“I think about that more than the literal view of the landscape,” he says. “I don’t think of myself as a landscape representational artist. I think about quantum mechanical flow forms, magnetic fields and gravitational fields.”

In some cases, Diepenbrock’s pieces will take three to five months to figure out a final presentation for a competition for a public project.

“It’s slow and it takes a long time to develop something for a site-specific place,” he says. “It takes that and a bit longer to actually build the work.”

In looking forward, Diepenbrock looks to push the scale of his work.

“The basic use of copper and steel will always be there,” he says, adding he also has an interest in working more with suspended compositions.

“There will be more movement,” he says. “Using dichroic glass and the pieces will be more optical and more about motion.”

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Capturing the Essence of Steampunk

- Peter Diepenbrock: Bringing Copper's Classic Beauty to Modern Sculptures

- James Reynolds: Drawn to the Inherent Beauty of Copper

- Adding a Modern Twist to Their Family's Legacy

- New Works by Wendell Castle Unveiled at Columbus Circle in NYC