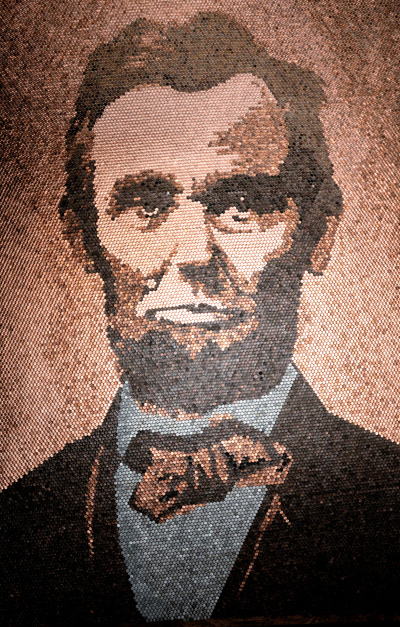

Abraham Lincoln, Reimagined Through Pennies

Richard Schlatter's A. Lincoln is comprised of more than 24,000 copper pennies.

Richard Schlatter's A. Lincoln is comprised of more than 24,000 copper pennies.Photograph courtesy of Richard Schlatter.

It would be putting it mildly to say that 2017 has been dramatic for Richard Schlatter. This veteran ad man went from a peaceful existence as a semi-retired graphic designer to finding himself, at 72, on the threshold of a new chapter as a large-scale fine artist.

Schlatter seems as surprised as anyone by what’s happened.

“I’m not even a fine artist, and I had no intention of entering Art Prize, but one day my creative brain just took over,” he recalls. Honestly, I never imagined ending up where I am right now.”

Schlatter created A. Lincoln, a monumental 8’ x 12’ portrait of Abraham Lincoln, composed entirely of pennies. The final piece weighed in at about 400 pounds, comprised of more than 24,000 pennies, ingeniously placed according to their varying hues.

Schlatter conceived of the project in a flash of inspiration, and then meticulously designed and built it over three fevered months. The process was punctuated by various setbacks and doubts —several of which almost derailed the endeavor. But, in the end, A. Lincoln triumphed the underdog Grand Prize Winner of the celebrated Art Prize, bringing Schlatter a $200,000 award as well as fame and a redefined career.

According to Schlatter, it all started one day last winter when he’d dumped out a bunch of pennies on the table and was preparing to take them to the bank. Suddenly, he was struck by all the different colors.

“Especially the real dark ones. I couldn’t stop looking at them," he recalls. "There was a such a range. I’m a big fan of Lincoln and I thought about the portrait, how cool would it be to make a portrait of Lincoln with all the heads-up pennies?”

Once the seed had been planted, Schlatter couldn’t stop thinking about the idea. He began searching the internet for different portraits of Lincoln.

“I found one I liked, but it was really low res,” he recalls. “When you blow up a low res image to 8 by 12 feet, it looks really pixilated, which was actually okay because it helped me narrow down the colors I would need to five different shades, so I started gathering and sorting.”

He sorted the pennies by color, and immediately realized that a big challenge would be getting enough pennies in each shade. He realized that uncirculated pennies would work for the facial area, and he was able to get a lot of those from his bank, but he needed some even lighter ones for the shirt and collar. That’s when Schlatter remembered something he’d learned as a kid: during WW2, pennies had briefly been made out of steel, so they looked silver, like dimes, although they were actually pennies. These he was eventually able to get from a collector. Other pennies came from friends and family. One of the many cool stats Schlatter related about A. Lincoln, is that if you take into account the circulation of each penny he used, over 173 million people have probably touched the portrait.

Richard Schlatter working on A. Lincoln.

Richard Schlatter working on A. Lincoln. Photograph courtesy of Richard Schlatter.

The color variations that inspired Schlatter were certainly the result of the varying copper content of pennies during different stages of history—zero in the steel pennies of WW2, 97% in most pennies through 1982, and just a minimal amount of copper plate today. But the variation also comes from the way copper darkens as it ages, which adds a richness, warmth and nuance to the overall look that could not have been achieved with any other metal.

Schlatter stresses that contrary to what many viewers assumed (because of the clarity of the final image), the pennies had not been painted or colored in any way. Except for cleaning the steel pennies to make them their lightest—through a painstaking process of wiping each one with water and lemon juice—the pennies were unaltered.

When he finally amassed the pennies he needed in all the right hues—including every year from 1909 through 2017, and built a frame with the help of a carpenter, Schlatter began actual assembly on the auspicious date of Lincoln’s birthday—February 12. The task in front of him was daunting.

“I didn’t know when I started how long this was going to take me. All I knew is that I had a bucket of pennies," he says. "It overwhelmed me. I even thought I might have to wait ‘til next year. Then I started to work on it, probably 45-50 hours a week, and started to see it take shape. I realized that if I worked day and night I could maybe get it done in a couple of months.”

The work was strenuous, done mostly from a high ladder, and Schlatter felt increasingly worn out. His back problems accelerated and he made several trips to the chiropractor for the pain. About halfway through the process, he was on the verge of giving up. But, he kept going.

The competition was stiff with 1700 Artists exhibiting work in different spaces all over the city of Grand Rapids, and excitement was running high. Schlatter said he felt people’s enthusiasm and began to be a little hopeful about his chances in the 2-D category, but when results were announced, he was floored to find out that not only won had he won the 2-D category, he’d won the Grand Prize.

Now, in a very different place than he was a year ago, Schlatter is pondering his options. People are not only expressing interest in A. Lincoln but are approaching him about commissioning new large scale projects. But Schlatter is taking his time before deciding on next steps, thinking things over as he takes stock of the incredible year he’s just had. “One thing at a time,” he says.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Harry Bertoia’s Sound Sculptures

- The Continuing Legacy of Sustainable Jewelry

- Maine Copper Studio

- Abraham Lincoln, Reimagined Through Pennies